A screenplay is an entirely different beast than a novel, essay, or poem. Instead of a finished work of art, a screenplay is a blueprint for a final product — and yet it still requires artistry. The modern screenplay has strict formatting requirements and conventions. Before you become the next great screenwriter, you need to know the rules of the medium, where they come from, what forms they take, and how they’re used. In this ultimate guide, we’ll cover the history of screenplays, their elements, and their types. Let’s jump in.

What is a Screenplay

A quick screenplay definition

If you want to make that transition from writing to scriptwriting, you have to know what a script is. Let’s define screenplay.

SCREENPLAY DEFINITION

What is a screenplay?

A screenplay is a written work for a film, television show, or other moving media, that expresses the movement, actions and dialogue of characters. Screenplays, or scripts, are the blueprint for the movie. A screenplay is written in a specific format to distinguish between characters, action lines, and dialogue. The formatting is also used to guide the budget and schedule for its production.

PROPER SCREENPLAY FORMAT INCLUDES:

- Scene headings (aka slug lines)

- Action lines

- Character names

- Dialogue

- Parenthetical(s)

Before we get into the formatting of a screenplay, let’s take a quick look at the history of the medium.

What is a screenplay definition

History of the Screenplay

Because screenplays are essentially outlines for a cast and crew to follow, the history of screenwriting is closely aligned to the history of film production. The modern screenplay, and the modern mode of moviemaking, isn’t as old as you may think.

Scenarios (1895 — 1905)

The early years of film were filled with experimentation. Artists were figuring out what to do with the medium. What do you film? How is it structured? How do you present it to an audience?

It makes sense, then, that the written plans that accompanied these early films were more open-ended. Many filmmakers would write down a couple sentences about what they wanted to shoot. Films only lasted a few minutes, so a few sentences were all that was necessary.

These documents were called “scenarios.”

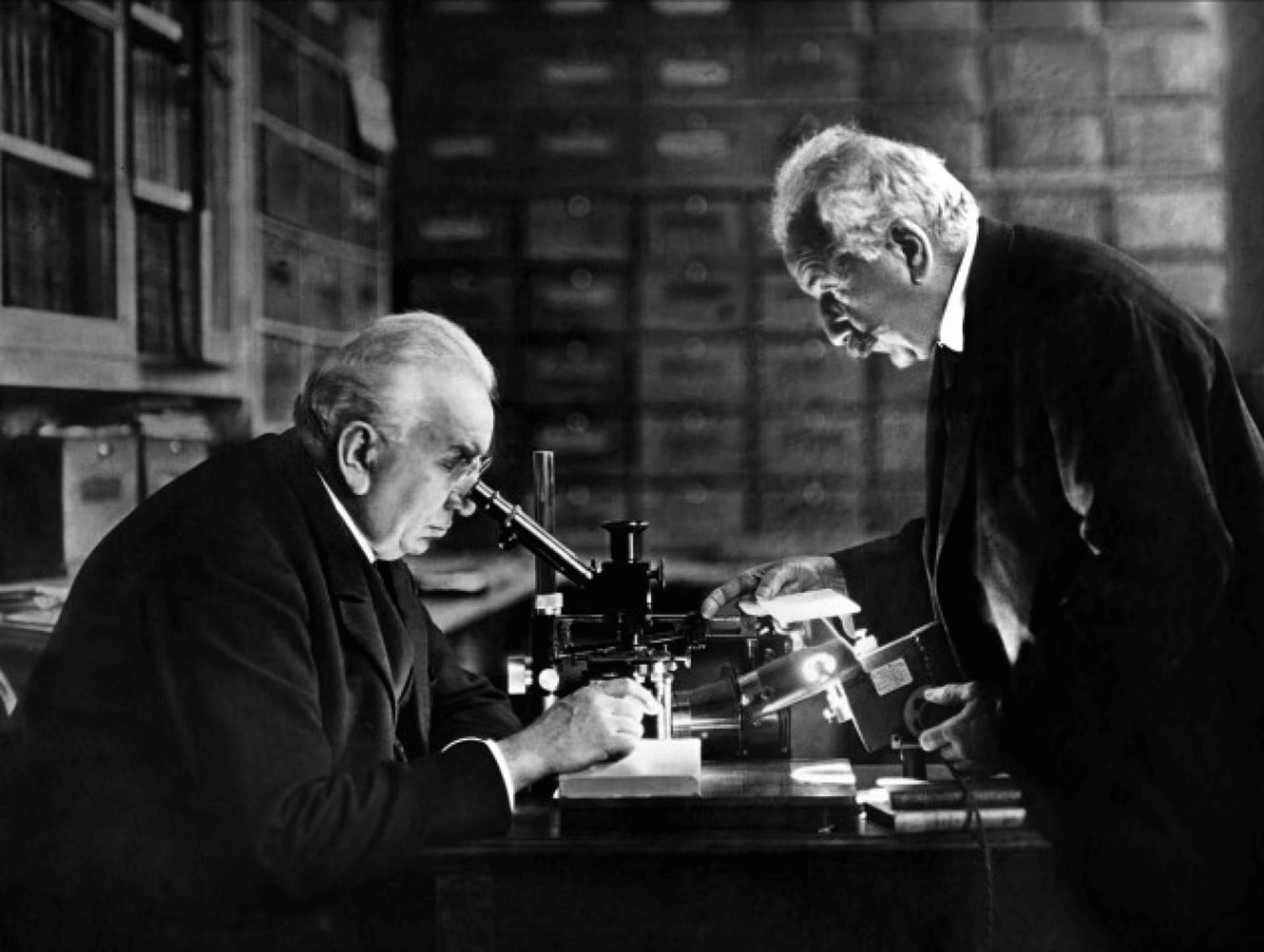

Lumieres at work

The Original Master Scene (1905 — 1920s)

As films became more involved, so did screenplays. Georges Melies’ A Trip to the Moon, released in 1902, had what is now considered one of the first screenplays. Unlike earlier works, Melies’ film had multiple, distinct scenes. So for his script, Melies wrote a small description for each scene.

Trip to the Moon

A year later, Edwin Porter continued to formalize the writing process with The Great Train Robbery. The filmmaker wrote lengthier descriptions for each scene, and formatted these descriptions in a manner that is now called the Master Scene script.

The Continuity Script (1920s — 1948)

Experimentation continued to flourish through the remaining years of Early Cinema. In the 1910s, a few business-minded individuals realized that this experimentation and creative freedom wasn’t actually very economical.

Instead, men like Thomas Ince began to re-mold the filmmaking process, inspired by efficiency-obsessed industrialists like Henry Ford. Film studios began cropping up, and these studios took an assembly-line approach to making movies.

Thomas Ince

The script now became critically important for executive control. With a detailed blueprint for what would be shot, studio heads could greenlight pictures knowing exactly how much it would cost, how long it should take, and what the final product would look like.

This resulted in screenplays that were much more elaborate – they would include what shots would cover what moments and where the editors would cut. The production crew would then know exactly what to do – no inefficient creative ideation.

This script format was called the continuity script. Because sound was introduced in 1927, it was this format which first began to incorporate dialogue as well.

The Master Scene Script (1948 — Today)

As studios grew more powerful, they got on the wrong side of the US government – specifically, its antitrust laws. Because studios owned everything from pre-production to distribution (studios owned theaters), they had become vertical monopolies.

In 1948, the Supreme Court decided enough was enough, and ruled against the studios. The end of the studio system was nigh.

A new system began to emerge. Now that filmmakers had more freedom, they became more powerful. Auteur theory began to take hold – a film could be credited to a singular vision.

Now, producers would put together “packages”: a director, some stars, and a screenplay. These packages would then be sold to studios.

So what did this mean for screenplays? First, it meant that the continuity script was out the window. Directors chafed at being told what to do by a pesky screenwriter (unless that screenwriter was themself).

It also meant that a writer’s screenplay was a proof-of-concept, a product to be sold. As such, screenwriters began to prioritize readability and, in turn, sell-ability. This meant economic writing and prioritizing story over production details, but those would come later in the process.

This was a new form of the master scene script, and it’s the form writers continue to use today.

Of course, this is a very simplified version of Hollywood history, and dates are blurry/disputed (script formats didn’t change overnight), but now you have a pretty good basic understanding of how we got to where we are.

What is a screenplay

Elements of a Screenplay

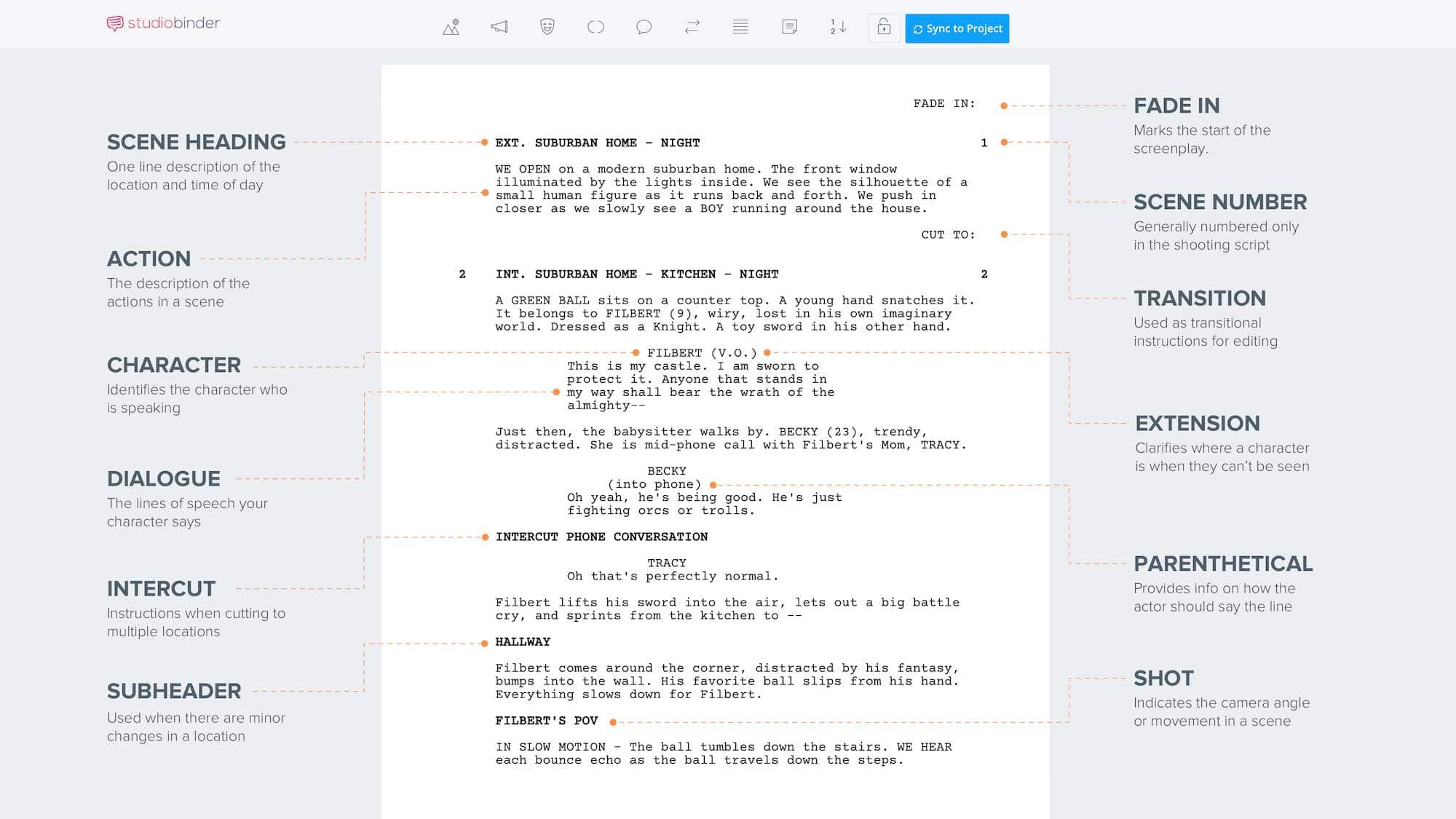

The elements of a screenplay come together on the page in a specific format. In the following diagram, you'll see the required elements and their basic layout.

Proper script formatting is a necessary evil. Movies are budgeted and scheduled directly from the script length, how many scenes are on a single page, etc. This is why understanding and implementing format is so crucial.

Follow the linked image below to see a sample script, including formatting and required elements using StudioBinder’s screenwriting software:.

Screenplay elements and layout • Screenplay meaning

As you can see, each element has defined parameters on the page. Let’s break these pieces down.

Scene Heading

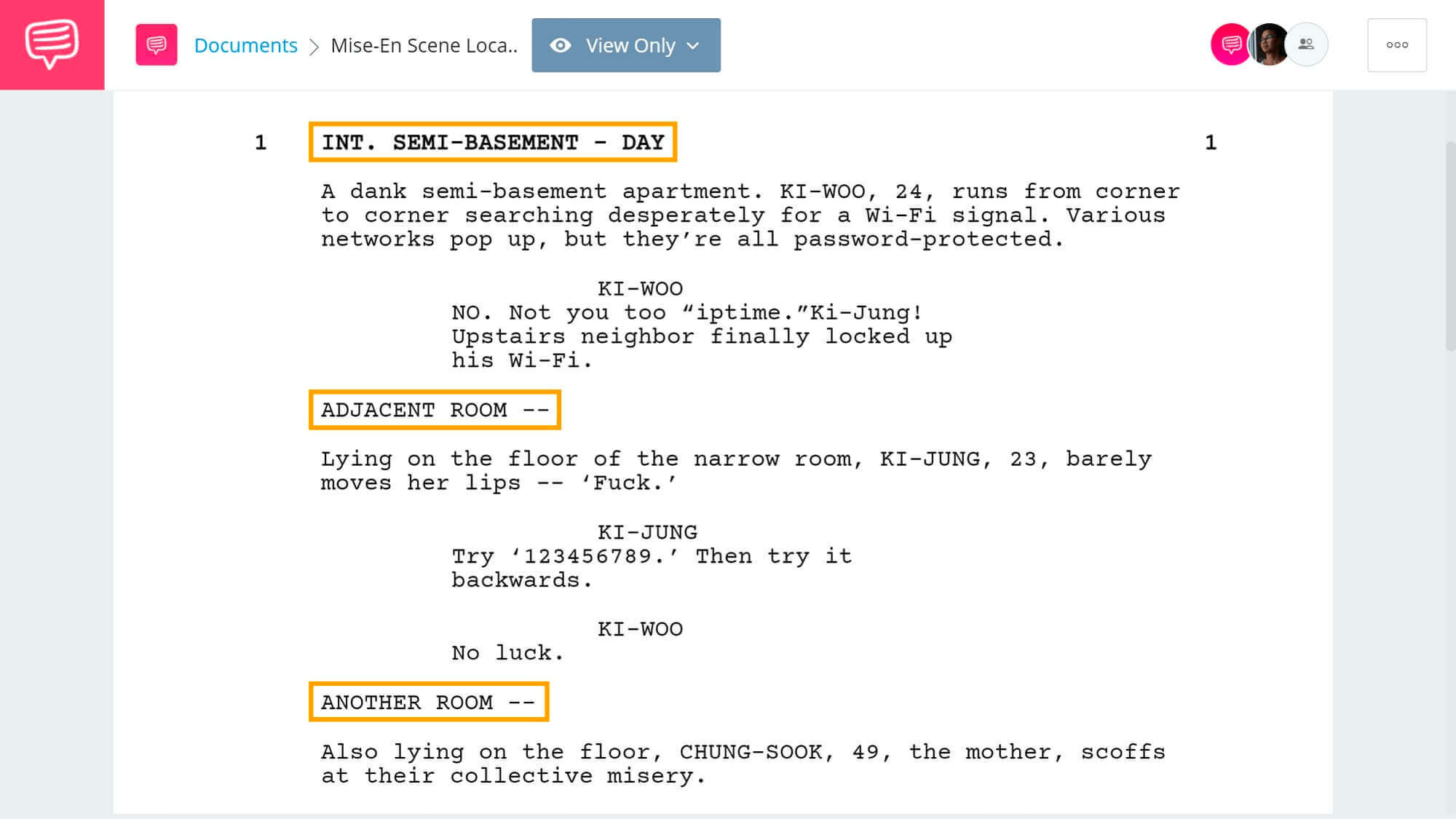

Also known as a slug line. This is where you put the most practical and immediate information about your scene: When and where.

Start with where. First, is your scene inside or outside? If inside, write “INT.” for interior. Outside, write “EXT.” for exterior. Do you think yours is both – like two characters are talking, one on the doorstep, one inside the house? There’s something for boundary-breaking writers like you: “INT./EXT.”

Then, we get more specific. You’re inside where? This can be as simple as “CHURCH.” You can also give some more information, if it’s important or if you have multiple churches, like: “CATHOLIC CHURCH.”

Next, add your time of day. This comes after a dash, and can refer to the time of day or the relationship to the previous scene. For example, you can write “NIGHT” or “MORNING,” or you can say “CONTINUOUS” (immediately after the last scene) or “LATER.” There are plenty of other options.

Slug line and subheadings • Screenplay meaning

Like the example above, you can use sub-headers to change locations within the main location (e.g., different rooms in the same house). Or these sub-headers can also help redirect the reader to different characters or conversations occurring in the same scene.

Action

This is where all your non-dialogue stuff goes. Set description, character description, actions – it all goes here. There are a couple rules of thumb for action that extend beyond its formatting.

First, write in third person POV and always in present tense.

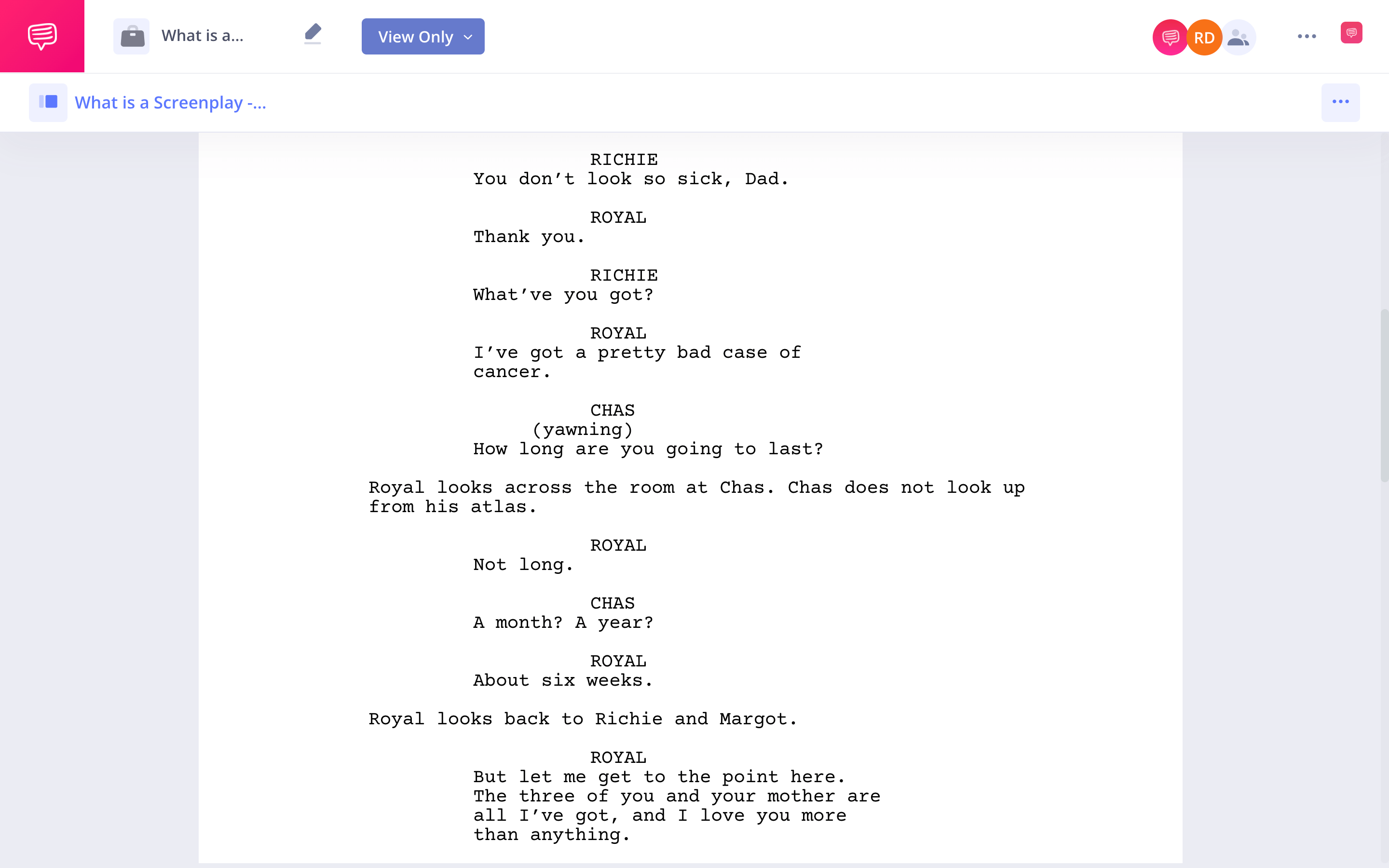

Take a look at this scene from The Royal Tenenbaums.

Royal Tenenbaums script pdf • What is a screen play

As Wes Anderson and Owen Wilson show us here, it’s good to keep it brief. Write just enough that the reader gets the necessary information. Instead of “The spot light is brighter than the sun, its beam violently shining upon Gerard’s skin,” go for “the bright spot light shines on Gerard.”

This rule can be broken occasionally: if the spotlight is a big plot point (maybe Gerard is allergic to light), then the former may be acceptable.

Third, keep it visual. If the camera wouldn’t be able to see it, it’s best not to write it. For example, the following is a no-no: “Gerard thinks of his mom as the light boils his skin. What would she think of him now? If only he hadn’t lost her to that freak Pottery Barn accident.” This is all interior; save it for the novel.

There are some times when this rule, too, can be broken. You may write, “Gerard boils under the light. Every hardship has led to this point.” That second sentence is technically not a visual, but it indicates to the actor that this is a crucial beat for Gerard, and tells the director to linger on this moment. Of course, use this sparingly.

Some things in action need to be put in uppercase, like the following:

Character’s name the first time they appear

Key details/props

Specific shot

All caps draws our attention to these important elements.

Character

Also referred to as character cue. A character’s name should be in uppercase before their piece of dialogue.

In action, however, a character’s name can be written normally after their introduction.

Dialogue

Dialogue occurs under the character cue. Parentheses next to the character’s name can indicate voice over (V.O.), off-screen (O.S.), or pre-lap (when a character begins speaking before a scene starts).

Parenthetical

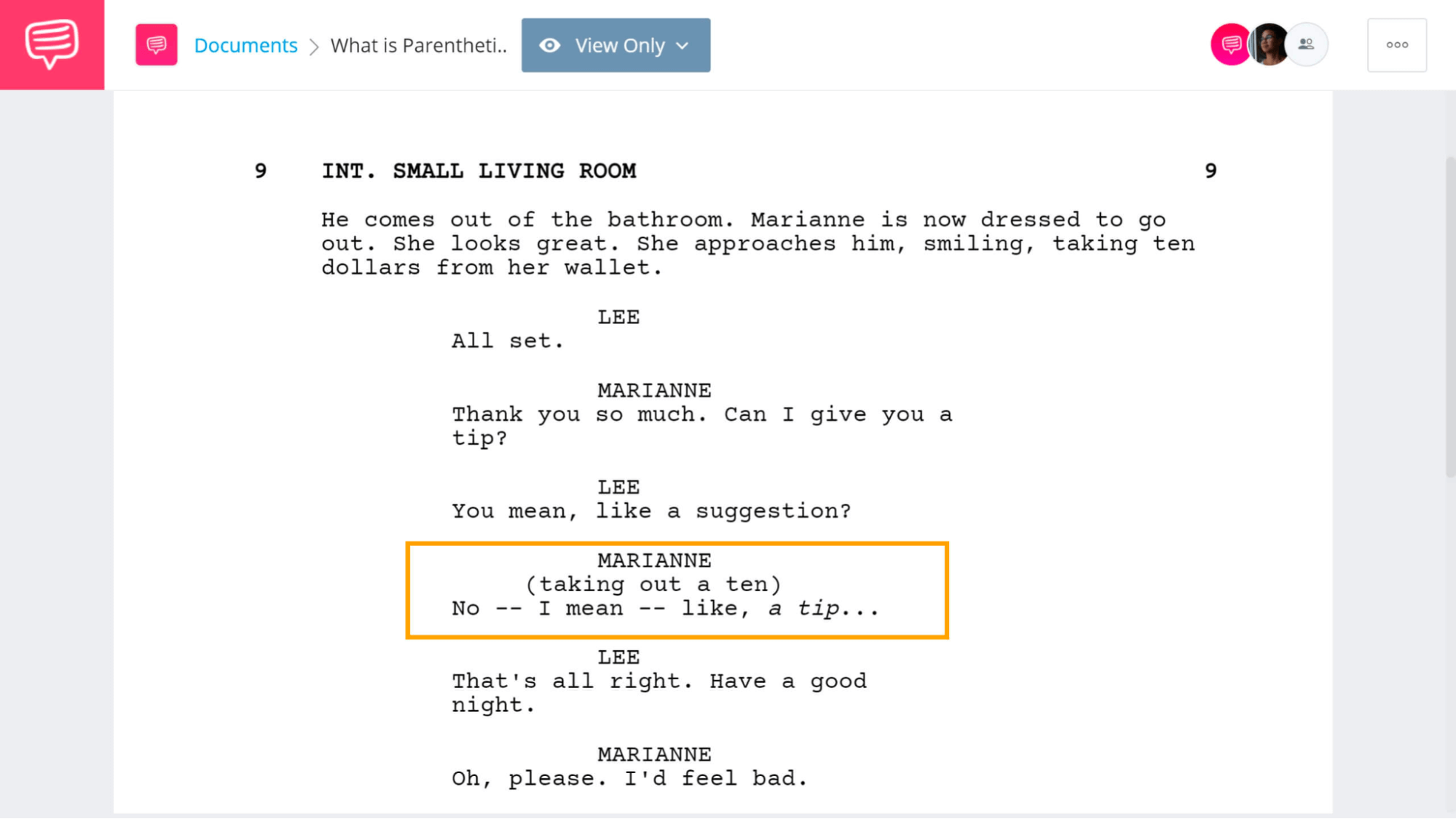

Parentheticals under a character’s name are used for performance notes. Use these sparingly, both for readability and to avoid annoying an actor. If a character’s line is, “Son, unfortunately no one can make it to your birthday party,” you don’t need a parenthetical saying “(Sadly).” Actors know how to interpret lines– that’s their job.

If it’s unexpected, and not discernable in the line, that’s when a parenthetical. For example, if you want the aforementioned line to be kind of teasing, you could write, “(insincere).”

Parentheticals in screenwriting • What is a screen play

Parentheticals are also helpful in scenes with a large group of people talking. If it’s confusing who a character is speaking to, you could include, “(to Gerard).”

Parentheticals can be used for pacing. If a character has a long line and there’s a moment where a sentence should sink in, you could write, “(Pause),” or “(Beat)” if there’s an emotional shift. Again, use this sparingly – a good actor with good writing will know where to pause.

Transition

Transitions can be seen as vestigial organs, left over from the days of the continuity script. A transition may look something like, “CUT TO:” or “SMASH TO:” or “MATCH CUT TO:” on the right side of the page.

But just as actors don’t like too many parentheticals, an editor doesn’t love too many transitions. A “CUT TO:” at the end of a scene may be unnecessary. Of course we’re cutting to the next scene.

A transition should only be indicated if it’s crucial to the story. Maybe a character says, “There is absolutely no chance I get on that horse. I’d rather die than ride that horse,” and in the next scene the character is on the horse. There, you could use a CUT TO: to punctuate the joke.

RELATED POSTS

What is a Screenplay

Screenplay vs. Script

So now you know how to write a screenplay. Or is it a script? What’s the difference? While there is technically a difference between screenplay and script, we should note first that they’re often used interchangeably, even by industry professionals.

But technically speaking, a screenplay is a more filled-out version of a script. A script is usually what is being sold – it’s prioritizing readability and story, not production details.

A screenplay is to a script as Charizard is to Charmander. A screenplay is what the script will evolve into by the time production comes around. It has more details and more information for each production department.

Think of it as something closer to a continuity script (yes, we realize the use of “script” here is confusing).

We should also add that the term “script” is a bit more vague than screenplay. A script can be a blueprint for a variety of artforms: video games, theater, new media, etc. A screenplay, however, only relates to a television show or movie.

So the difference between screenplays and scripts has been solidified, but our work isn’t done. There are subtypes to look at.

What is a screenplay

Types of Screenplays

Just as there are different stages of making a movie, and different ways to make movies, there are different types of scripts.

Spec Script

During the studio system, writers worked as permanent employees for companies, churning out scripts on a regular basis. But after the studio system’s collapse, writers became freelancers, hopping from project to project without any guarantee of steady employment.

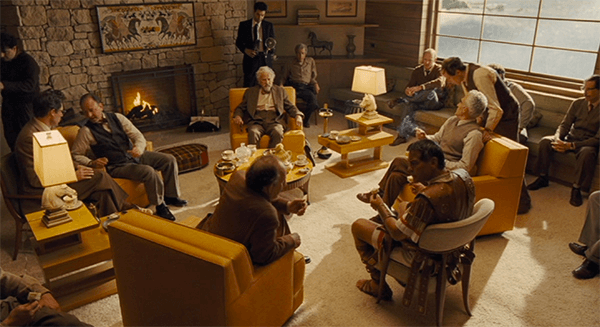

Studio screenwriters in Hail, Caesar • Define screenplay

This resulted in the rise of the spec script. Spec is short for speculative, and the script refers to a work written without any deal with a studio or executive. In short, it’s a script which a screenwriter is writing for free.

A spec script is essentially a gamble. A writer puts untold hours into a screenplay just in the hope that it might get sold. Sure, the pay day may come, and it may be huge, but it’s certainly not a given.

Most writers aren’t strangers to spec scripts, especially screenwriters looking to enter the profession. A beginning screenwriter with few or no credits to their name will have a hard time getting money up front to write a script.

Commissioned Script

A commissioned script is the opposite of a spec script. Here, a production company has paid a writer to write a specific story. It’s guaranteed money, though, of course, the writer usually doesn’t have the freedom to write whatever they want.

Pitch Script

A pitch script usually isn’t really much of a script at all. Instead, it’s a brief outline or treatment which summarizes the story a writer is proposing. Usually, pitch scripts are used when a studio has a preexisting property they are looking to hire a writer for. Instead of choosing one person immediately, they’ll hear some pitches from a variety of writers, and go with the idea they like the most.

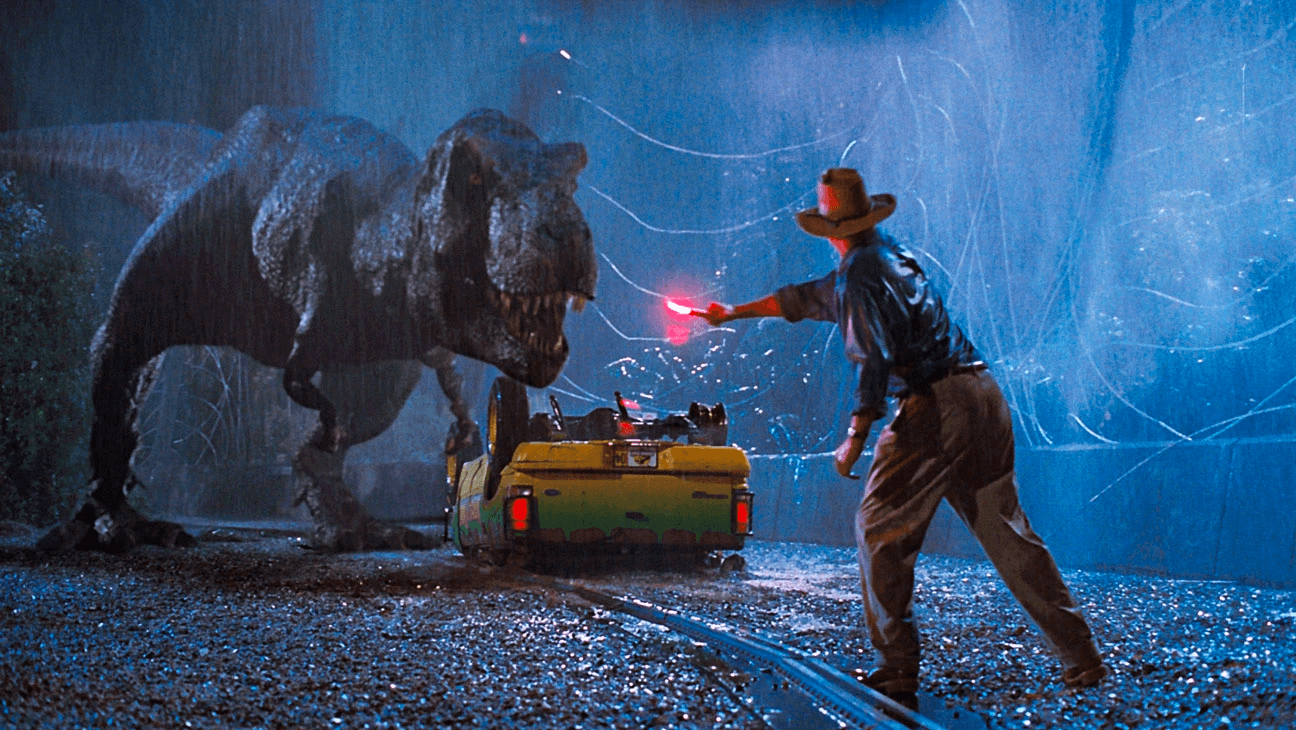

This happens a lot with sequels or franchise installments. Say your manager says Universal wants a pitch for a new Jurassic Park direction. You may pitch a story which takes place two hundred years in the future where the dinos have re-taken over the world, and your script follows a couple dinosaurs going to an amusement park where humans are the attraction. You’ve got a contract.

Jurassic Park, ripe for a million sequels • What is screenplay in a movie

Adapted Screenplay

This is a script based on an existing intellectual property (IP), such as a novel, play, or magazine article. These are very common, since it’s a far less risky endeavor to make a movie on something that has already proven to be popular.

Pilot Script

Television has scripts too! A pilot script is the most important script of a television show, since it’s what gets the show made or not. It’s the script for the first episode of the show, establishing the key characters and tone of the series.

The formatting for TV is similar to film, especially now that the two mediums behave more and more alike these days. Some TV scripts, however, explicitly notate where acts should break (i.e. END OF ACT I, ACT II:, etc.). This makes clear where commercials should be placed. Again, due to streaming, this isn’t always the case any more.

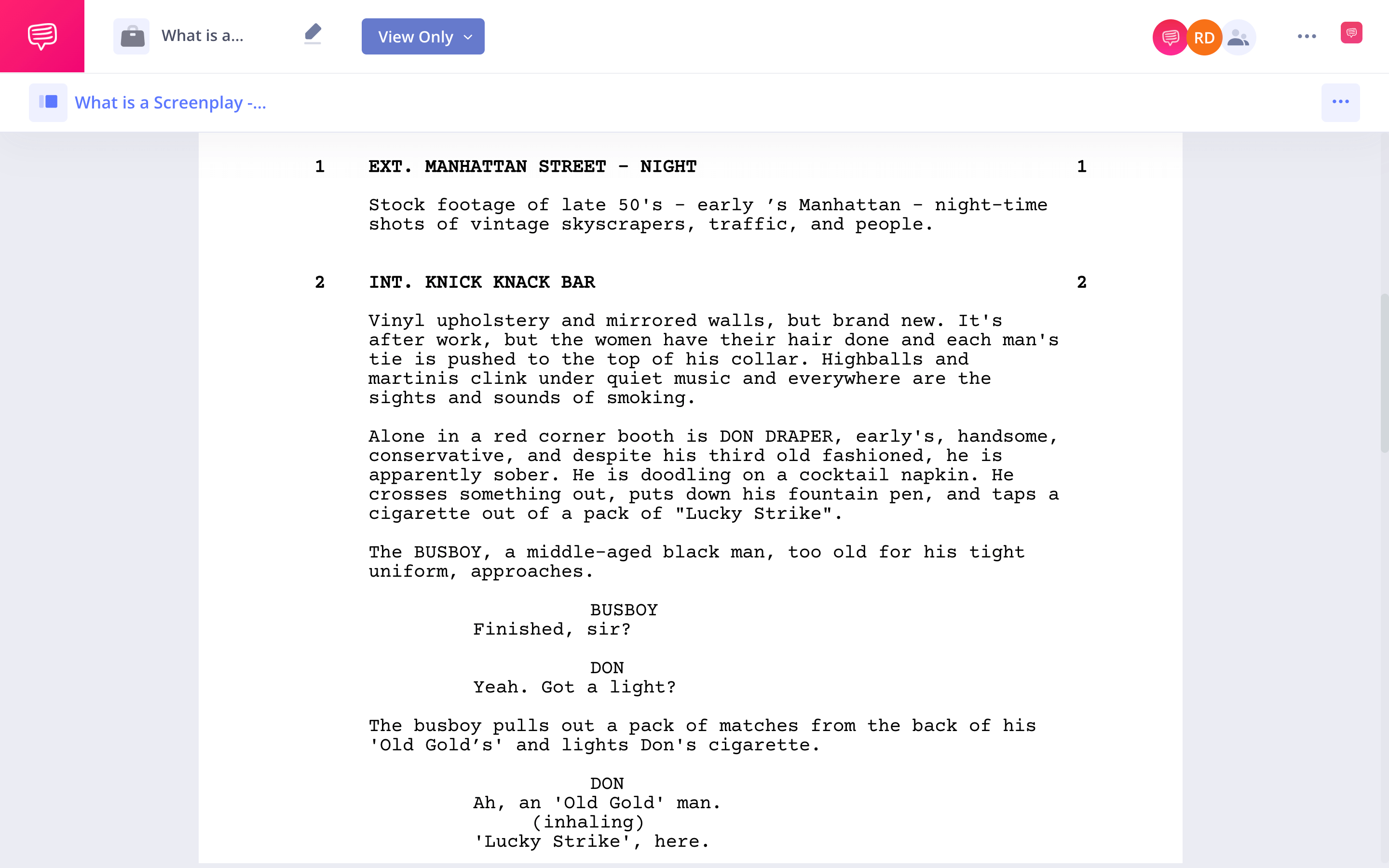

Take a look at the opening of the pilot for Mad Men:

Mad Men pilot

Matthew Weiner notes the act first, and then gets right down to business, establishing the setting in which most of the series will take place.

TV pilots are often presented with a pitch deck that further elaborates on the characters and season/series arc for the show, since these things may not be self-evident in the first episode.

A pilot’s length varies based on genre. For a half-hour comedy, a script is about 25 to 35 pages long. For an hour long drama, a script is often 50 to 60 pages. There are exceptions to both rules.

What is a Screenplay

Screenwriting Software

Do all these formatting rules and conventions have you stressed out? Are you staring at a Word doc trying to indent for a piece of dialogue and feeling like you should take your dad’s advice and apply to law school instead?

Fear not. Very, very few screenwriters format themselves. There are tons of screenwriting software options that can do that work for you.

StudioBinder

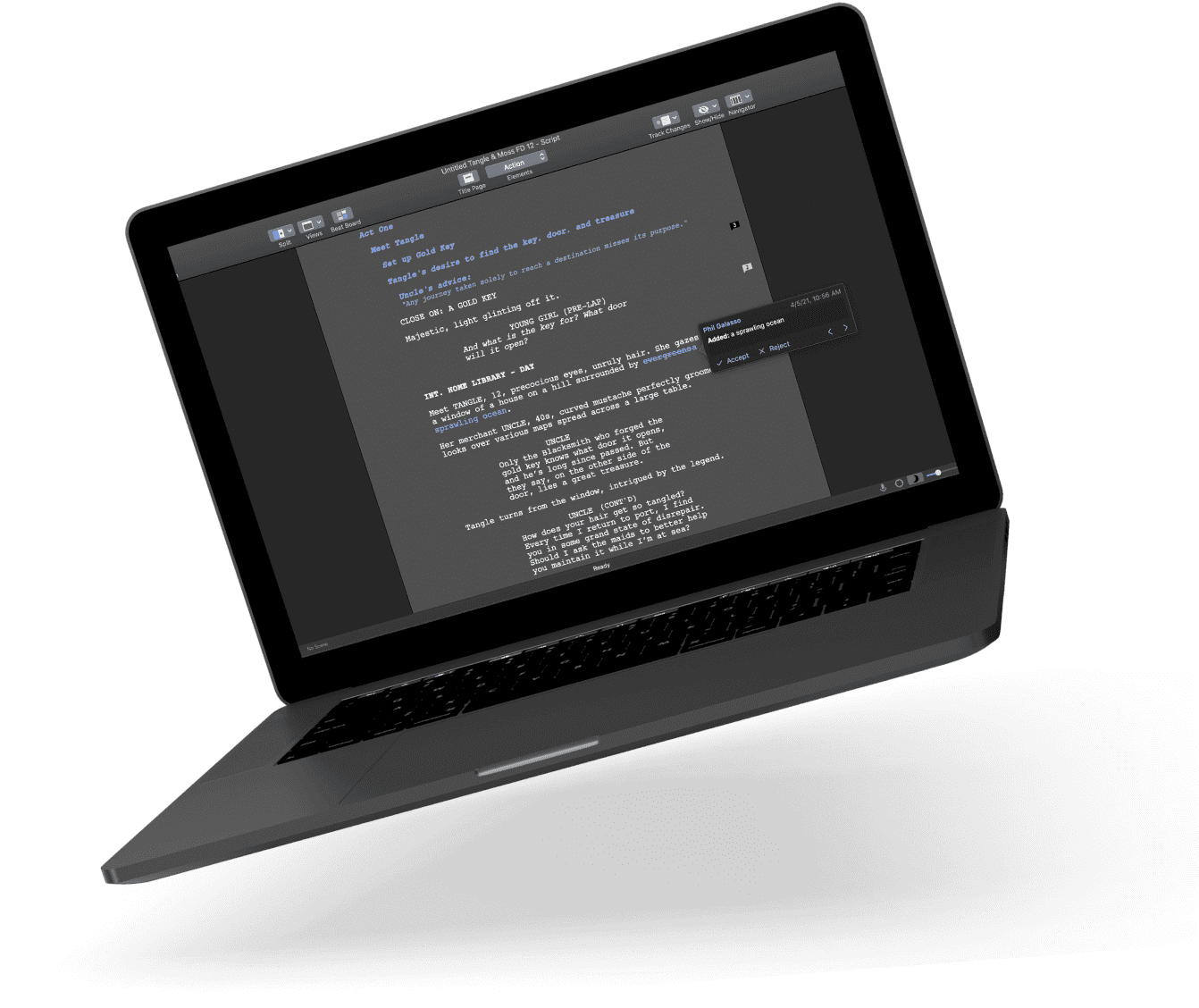

Here’s the path of least resistance, since you’re already on our site. StudioBinder’s screenwriting software will help you make a professional-standard script, and also makes it easy to collaborate with other writers on the same doc.

We also have shot list, storyboarding, and other production services on our platform, so it can be a one-stop shop for a multi-hyphenate. Plus, it’s free to get started.

StudioBinder for all! • Subscribe on YouTube

Final Draft

Final Draft is a go-to for many screenwriters. It’s one of the oldest softwares out there, and costs a pretty penny for that name recognition.

Still, it’s a great, no-frills tool that certainly gets the job done.

Final Draft • Screenplay of a motion picture

Celtx

Celtx is another great option for aspiring screenwriters. Celtx has some really helpful perks, like Read-Through, which reads back what you’ve written. Welcome to the future, folks.

Squibler

Squibler boasts the most whimsical name of the software options. If that isn’t enough to sell you on it, Squibler’s got a super simplistic interface which lets all your focus go into your writing which, as a writer, is where you want it to go. It’s also pretty cheap.

Writer Duet

As its name indicates, Writer Duet is all about collaboration. All of its features revolve around your script being shareable and open for edits in real-time. It’s a great source for writers who are team players.

Now that we’ve given you the software, you’re ready to write your script. Don’t let readability, sellability, and all the other -bilities bog down your process. You’re writing because you’re a storyteller. Tell your story.

Up Next

How to write a movie script

In this next post, we'll go into further detail about the required elements like scene headings and action/description, and industry standard screenwriting format. We'll also answer some general questions that every screenwriter has (e.g., How long should my script be? Do I need a cover page?). Let's get to it!